The rollout reality

Every safety manager knows the pattern. A new procedure gets announced with fanfare. Training sessions are delivered. Posters go up. Forms get signed.

Then, slowly, old habits creep back. Within months, you're back where you started – except now there's a documented procedure that everyone's ignoring.

This erosion is frustrating for any safety initiative. But for vehicle-pedestrian controls, it's potentially fatal.

The stakes couldn't be higher

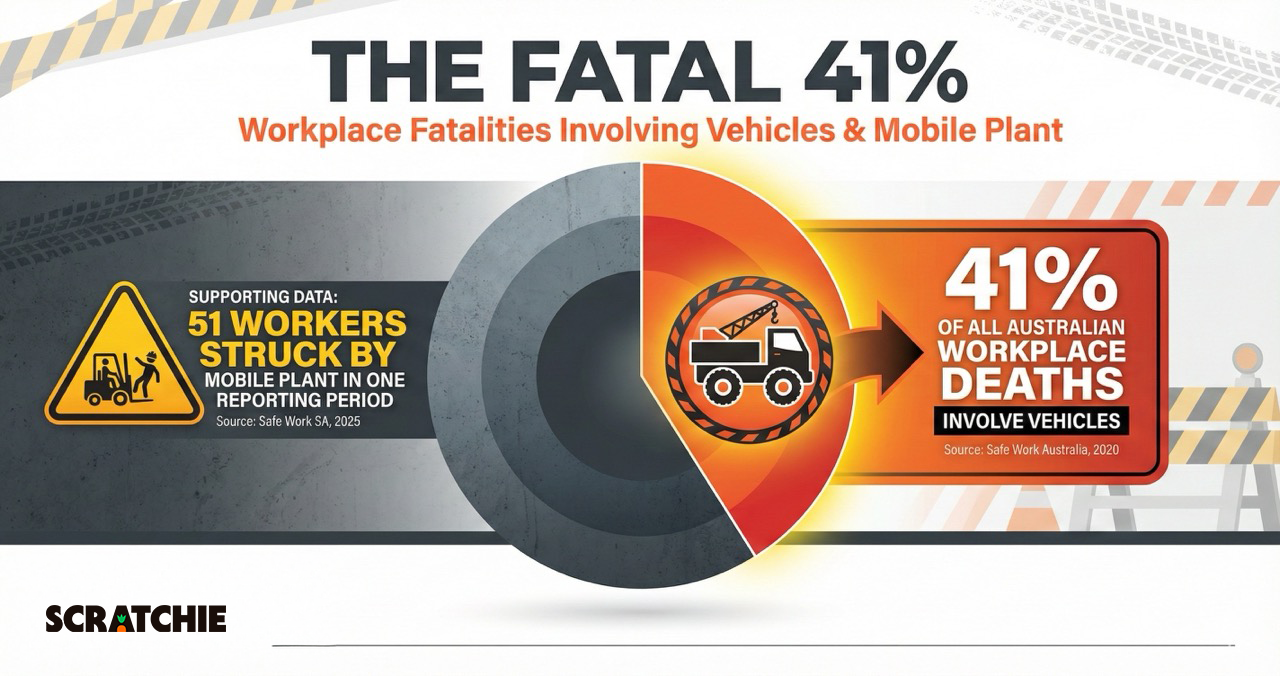

In Australian workplaces, vehicle collisions account for 41% of all worker fatalities – the single largest cause of death on the job (Safe Work Australia, Work-related Traumatic Injury Fatalities Australia 2020).

In civil construction specifically, the risk is even more concentrated. Safe Work SA recently reported 51 workers struck by mobile plant in just one reporting period (Mobile Plant and Pedestrians Don't Mix, 2025). Every one of those 51 people went home that day only because physics was marginally on their side.

Unlike a building site where zones can be established and maintained, civil infrastructure projects – roads, rail, tunnels – are linear, dynamic environments. The plant-pedestrian interface shifts daily. Yesterday's safe path is today's swing zone for an excavator.

This is exactly the context where embedding new procedures is hardest, and where failure to embed them is most catastrophic.

Why punishment-based approaches fail

The traditional response to non-compliance is predictable: tighten the rules, increase the consequences. "Three strikes" policies. Instant dismissal for "Golden Rule" violations. Name the offender in the toolbox talk.

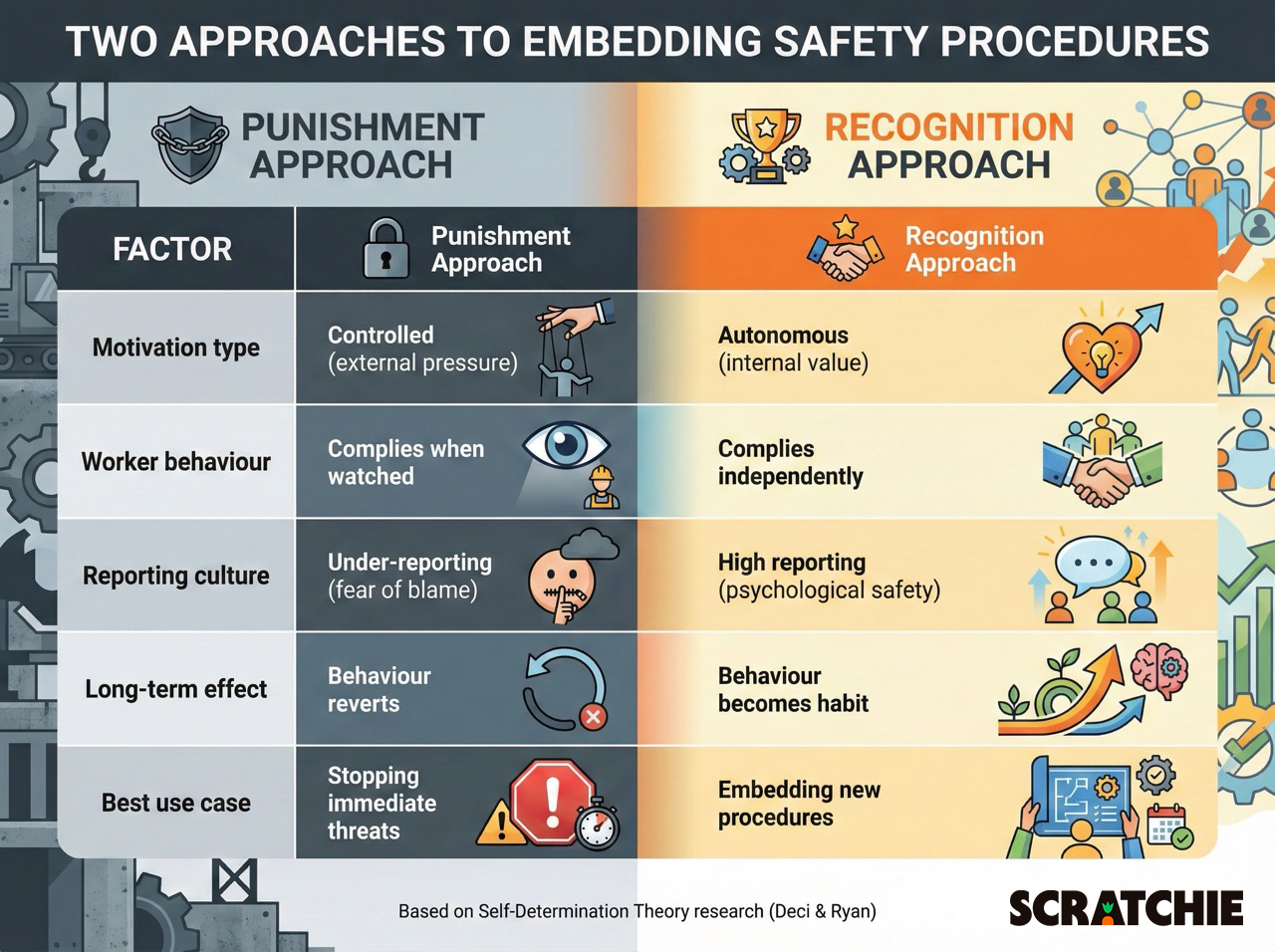

Research in behavioural psychology calls this "controlled motivation" – workers follow the rule because they have to, not because they want to. And it creates three predictable problems:

Workers hide errors. When reporting a near-miss means risking your job, near-misses don't get reported. The organisation is starved of the very data it needs to improve.

Behaviour reverts when supervision stops. Compliance exists only in the presence of enforcement. The moment the safety manager walks away, old habits return.

Culture becomes adversarial. Safety becomes something management does to workers, not with them. The "them vs. us" dynamic undermines every future initiative.

A 2024 study published in Frontiers in Public Health confirmed what practitioners already suspected: rewarding compliance is significantly more effective than penalising non-compliance, particularly for long-term retention of new procedures.

What actually works: autonomous motivation

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), one of the most validated frameworks in motivational psychology, explains why positive reinforcement works where punishment fails.

According to SDT research, workers are genuinely motivated when three psychological needs are met:

Autonomy: Workers need to feel they have a voice. Instead of imposing a new exclusion zone procedure, involve crews in designing it. When workers help write the rule, they're intrinsically motivated to follow it.

Competence: Workers need to feel capable. Positive feedback ("You set that exclusion zone up perfectly") builds professional mastery. Punishment ("You breached the zone") attacks competence and triggers defensiveness.

Relatedness: Workers care about their team. Framing safety as "looking out for mates" resonates. Framing it as "following company rules" creates bureaucratic distance.

Research on construction safety motivation found that autonomous motivation – driven by positive reinforcement – significantly predicted safety compliance. Controlled motivation – driven by fear of punishment – did not predict safety outcomes effectively (International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021).

From theory to practice: how leading contractors are making the shift

Several Australian Tier 1 contractors have moved beyond the compliance-punishment cycle.

Laing O'Rourke's "Next Gear" program represents a fundamental shift. Rather than investigating only accidents, they investigate success – asking "How did you go right today despite the difficulties?" This openness means workers trust management enough to say "This new procedure doesn't work in practice," enabling adjustment rather than silent non-compliance.

Cross River Rail's Human Factors program embedded new plant-pedestrian procedures through "Day in the Life Of" workshops. Instead of writing procedures in an office, they ran simulations with actual operators and maintainers. Workers "rehearsed" the new procedures and identified flaws before they went live – building competence and ownership simultaneously.

John Holland discovered that when safety became something workers could "win" at rather than merely comply with, the entire dynamic shifted. As their Operational Safety Manager, Josephine Taylor, described:

"For the first time, safety became something that our workers could actively 'win' at. The platform's gamification and instant rewards created a buzz of excitement and friendly competition among the team. It was heartening to see workers proactively looking out for one another."

– Josephine Taylor, Operational Safety Manager, John Holland (2024)

The measured impact was significant. Independent surveys showed a 25% improvement in safety attitudes when instant recognition was introduced – a finding consistent with academic research showing strong correlation between safety attitudes and safety outcomes (Scratchie Safety Impact Analysis, University of Newcastle partnership, 2023).

The transformation in action

At Buildcorp's Angel Place project in Sydney's CBD, Senior Project Manager Steve Taunton – with 43 years in construction – observed something he'd never seen before:

"We've had teams join us from similar projects with less-than-stellar safety reputations, but once they experienced the opportunity to earn instant rewards... their performance and commitment to safety have been exceptional."

– Steve Taunton, Senior Project Manager, Buildcorp (2024)

The project recorded no serious safety breaches during the Scratchie implementation period.

Perhaps more telling: 92% of workers surveyed said they preferred working on projects using recognition-based approaches over traditional compliance-only sites.

Three principles for embedding your next critical procedure

If you're rolling out a new plant-pedestrian control – or any critical safety procedure – consider these evidence-based approaches:

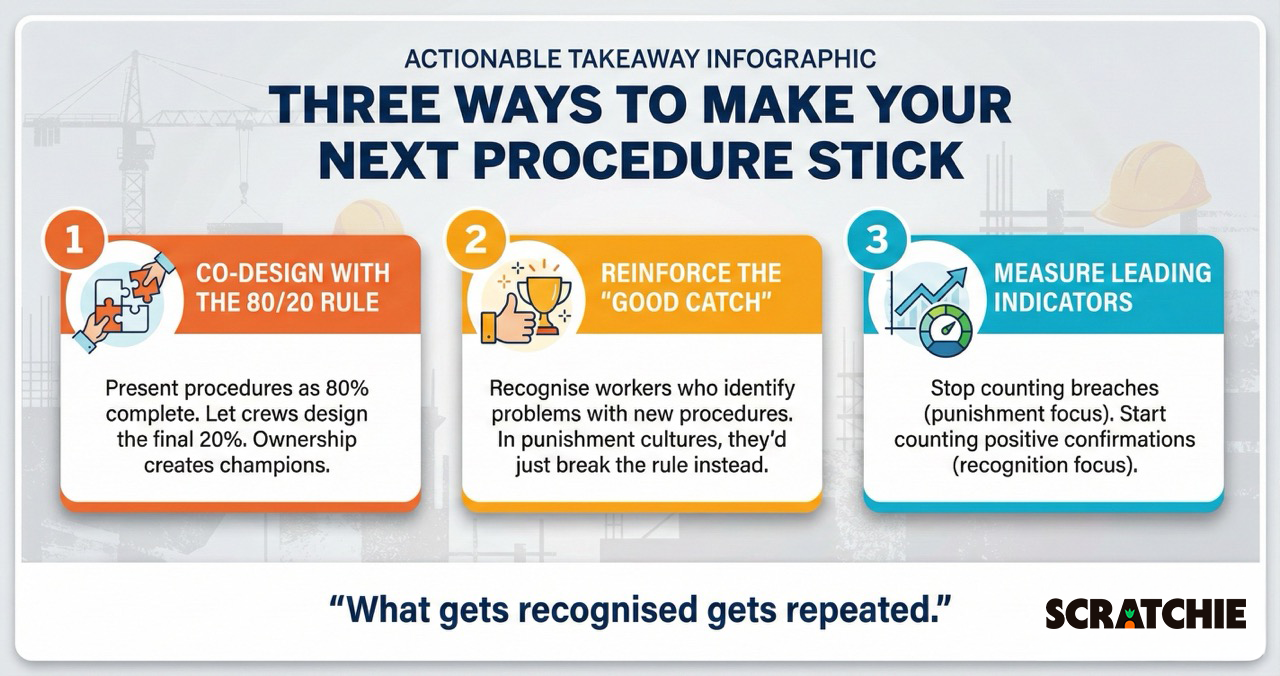

1. Co-design with the 80/20 rule

Don't launch a finished procedure. Present it as 80% complete and ask work crews to finish the final 20%. "We need a new exclusion zone protocol for the grader. Here's the draft. You map out where the physical barriers should go to make it workable."

This triggers ownership. Workers who helped design the procedure become its champions, not its critics.

2. Reinforce the "good catch"

Implement recognition for proactive engagement. When a worker identifies that a new procedure is difficult to follow in practice and reports it, reward them. In a punishment culture, that worker would simply break the rule to get the job done – and you'd never know until someone got hurt.

3. Measure leading indicators, not just breaches

Stop measuring "number of violations" (punishment focus). Start measuring "percentage of positive radio confirmations" or "number of exclusion zones verified correct" (positive reinforcement focus). What gets measured gets managed – and what gets recognised gets repeated.

The bottom line

Every civil contractor knows the vehicle-pedestrian interface is their highest-consequence risk. Every safety manager has experienced the frustration of watching new procedures erode back to old habits.

The research is clear: punishment creates compliance when watched. Positive reinforcement creates commitment that persists.

The contractors getting this right aren't just avoiding fatalities. They're building cultures where workers actively engage with safety because they want to – not because they're afraid of what happens if they don't.

That's the difference between a procedure that sticks and one that slowly fades to paper in a filing cabinet.

SOURCES REFERENCED

- Safe Work Australia (2020). Work-related Traumatic Injury Fatalities Australia 2020. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-11/Work-related%20traumatic%20injury%20fatalities%20Australia%202020.pdf

- Safe Work SA (2025). Mobile Plant and Pedestrians Don't Mix – Safety Alert. https://safework.sa.gov.au/news-and-alerts/safety-alerts/incident-alerts/2025/mobile-plant-and-pedestrians-dont-mix

- Frontiers in Public Health (2024). Safety incentives and compliance in construction. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1430697/full

- Glasgow Caledonian University (2021). Self-Determination Theory and Construction Safety Motivation. Published in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

- Laing O'Rourke (2016). An Award-Winning Approach to Safety: Next Gear. https://www.laingorourke.com/company/news/2016/an-award-winning-approach-to-safety/

- Acmena (2024). Cross River Rail Human Factors Program Case Study. https://www.acmena.com.au/case-studies/cross-river-rail-human-factors-program/

- John Holland (2024). Josephine Taylor testimonial letter.

- Buildcorp (2024). Steve Taunton testimonial letter.

- Scratchie Pty Ltd (2023). Scratchie Safety Impact Analysis. Survey of 140 workers conducted in partnership with University of Newcastle Centre for Construction Safety.

.svg)