The Turning Point

Put yourself in a sprawling auto parts factory in northeastern Mexico, 1995. Steam hisses from hydraulic presses. Sparks fly from welding stations. Workers navigate between massive stamping machines that forge steering gears and catalytic converters.

In this factory alone, 87 workers suffered injuries severe enough to miss work that year. Across Mexico's manufacturing sector, three out of every hundred workers were being disabled annually.1 Injuries weren't just statistics—they were expected, accepted, part of the job.

Then something changed. By 2003, that same factory - still running the same dangerous equipment, still producing the same automobile components - had virtually eliminated serious injuries. Lost-time accidents dropped from 87 cases per year to just 1.5.2

How does a workplace go from dangerous to nearly accident-free without changing its fundamental operations?

The Experiment That Changed Everything

In 1997, researchers Jaime Hermann, Guillermo Ibarra, and B.L. Hopkins from Universidad de Granada and Auburn University launched an ambitious safety intervention at this automobile parts manufacturing plant.2 What made their approach revolutionary wasn't just the methods they used; it was how they combined them.

While two sister plants continued with standard corporate safety protocols, the experimental factory implemented a comprehensive program that merged traditional safety methods with behavior-based safety (BBS) principles. But here's the crucial difference: they didn't just focus on frontline workers. They tracked and modified behaviors at every level, from line workers to managers.2

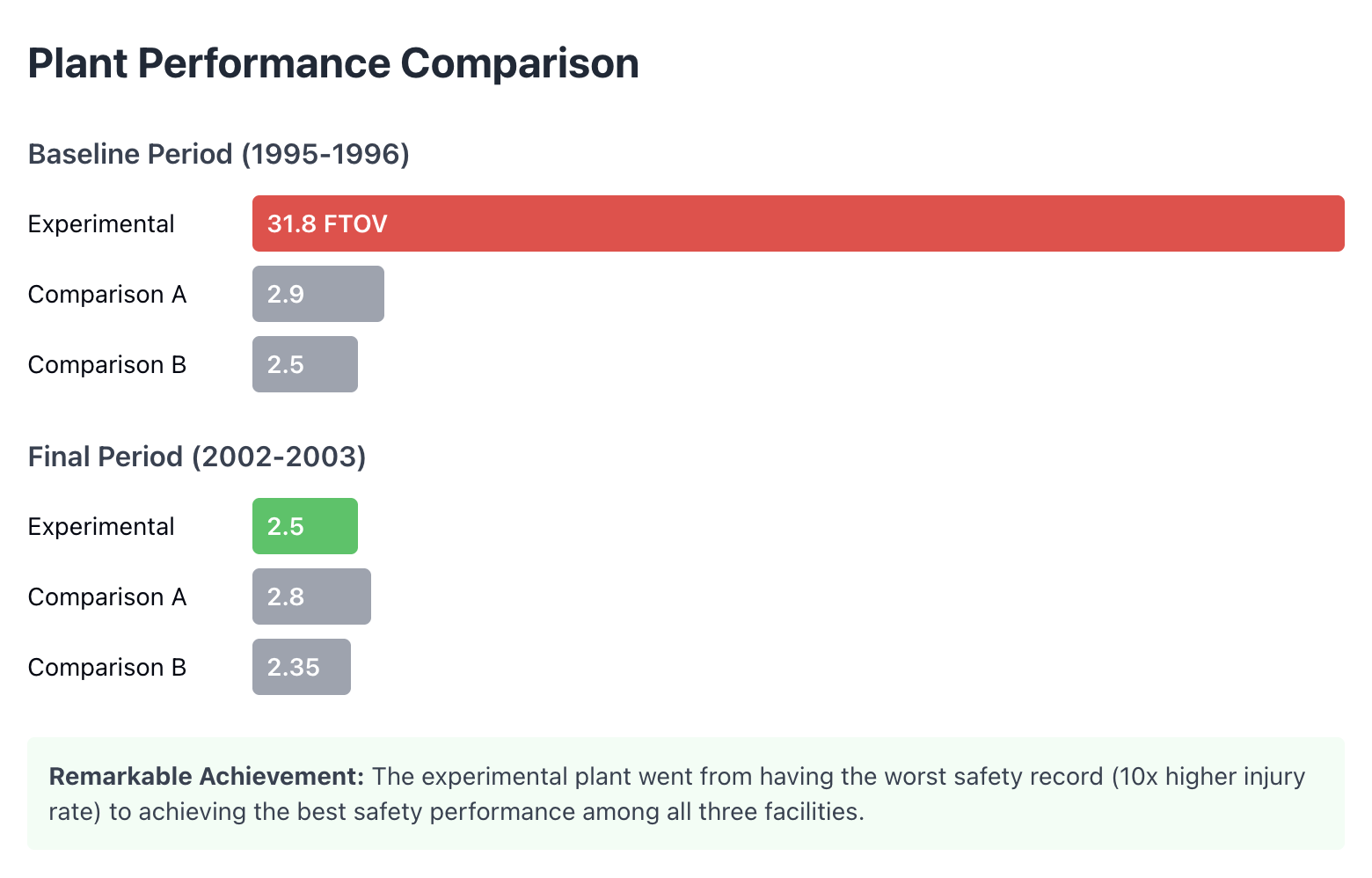

The results speak for themselves:

- 92% reduction in first-time occupational medical visits

- 99% reduction in lost-time case rate

- 96% reduction in severity rate (days lost to injuries)2

To put this in perspective: the baseline lost-time injury rates at the experimental plant were 980% to 1,150% higher than the comparison plants. By the study's end, the experimental plant's safety performance had not only caught up; it had surpassed both comparison facilities.2

The Power and Limits of Behavior-Based Safety

The success hinged on systematic behavior observation and modification: the cornerstone of BBS. Safety engineers conducted weekly unannounced observations using detailed checklists. Workers received immediate feedback for both safe and unsafe behaviors. Supervisors held weekly safety talks. Management tracked correction of unsafe conditions with military precision.2

As the researchers noted: "The fact that almost all of the yearly data collected for all three safety measures during the later years the experimental safety method was in effect were clearly lower than baseline data and the progressive nature of the declines in the safety statistics argue that the improvements are not simply the fluctuations of unknown origin that are common in safety data."2

But BBS has always faced criticism. Critics argue it focuses too heavily on worker behavior while ignoring systemic issues, essentially "blaming the worker" for management failures.3 The approach, rooted in B.F. Skinner's stimulus-response behaviorism, treats safety as a transaction: do this, get that.

The Mexican factory study addressed some of these concerns by expanding beyond frontline workers. As Hermann and colleagues argued: "BBS programs should expand to include behaviors that are distal to the behaviors of line workers and thus, improve its acceptance and effectiveness."2 They tracked management behaviors, safety audit completion rates, and corrective action timelines, making safety everyone's responsibility.

Why This Still Matters, And Why It's Not Enough

This study from the 1990s remains one of the most dramatic workplace safety transformations ever documented. It proved that systematic approaches combining behavioral intervention with traditional safety methods can achieve extraordinary results.

But workplaces have evolved. Today's employees — particularly younger generations — expect more than compliance-based systems. Research shows that workers experiencing autonomy in safety-related decisions develop internalized motivation that persists without external monitoring.4 Multiple studies demonstrate that job autonomy positively predicts safety performance, with autonomy explaining up to 44% of variation in safety outcomes.4

The limitation of traditional BBS becomes clear: while external rewards and punishments can change behavior, they don't necessarily create genuine commitment. Modern research in Self-Determination Theory reveals that sustainable safety culture requires satisfying three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness.4

The Evolution: From Compliance to Commitment

This is where modern approaches like Scratchie diverge from traditional BBS. Instead of surveillance and compliance, the focus shifts to recognition and empowerment. Rather than treating workers as subjects to be modified, they're treated as professionals whose expertise and judgment matter. The theory that underpins all this is known as Self Determination Theory5.

The evidence supports this evolution. Studies show that combining positive reinforcement with autonomy support creates more sustainable safety cultures. Workers transition from "I work safely to avoid punishment" to "I work safely because it aligns with my values."4 Organizations implementing this integrated approach report not just injury reduction, but enhanced safety climate, increased voluntary safety participation, and improved mental health outcomes.4

Consider the contrast: The Mexican factory achieved remarkable results through systematic observation and feedback - essentially benevolent surveillance. Modern approaches achieve similar or better results by empowering supervisors to recognize excellence and trusting workers to identify and address hazards.

The Bridge to Tomorrow's Safety Culture

The Mexican auto parts factory study remains a landmark achievement. It proved that systematic safety management, properly implemented and tracked, can virtually eliminate workplace injuries. The researchers deserve credit for expanding BBS beyond worker behavior to include management accountability—a crucial innovation.

But if a factory in 1990s Mexico could achieve 99% injury reduction using methods rooted in 1970s behaviorism, imagine what's possible today. Modern motivation science, combined with digital tools and evolved workplace expectations, opens new possibilities.

At Scratchie, we've taken the best lessons from studies like Hermann's — the importance of systematic implementation, regular feedback, and management engagement — and built them on a foundation of contemporary motivation science. Recognition replaces surveillance. Empowerment replaces control. The result? Safety outcomes that match or exceed traditional BBS, with the added benefits of improved morale, reduced turnover, and genuine cultural transformation.

The Mexican factory proved that systematic safety management works. Modern approaches prove that when you combine systems with human-centred motivation, you don't just reduce injuries—you transform workplaces.

Want to see how this evolution in safety thinking can work in your organisation? Let's talk about building a safety culture that honours both the lessons of the past and the possibilities of the future. Email hello@scratchie.com and we'll get back to you.

References:

- Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Información Estadística de Salud, 2004 ↩

- Hermann, J.A., Ibarra, G.V., & Hopkins, B.L. (2010). A Safety Program that Integrated Behavior-Based Safety and Traditional Safety Methods and its Effects on Injury Rates of Manufacturing Workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 30(1), 1-25. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8

- Frederick, J., & Lessin, N. (2000). Blame the worker: The rise of behavior-based safety programs. Multinational Monitor, 21(11), 10-17. ↩

- Multiple studies referenced in "Positive Reinforcement and Autonomy: Key Drivers of Workplace Safety Outcomes" - see attached research document for comprehensive citations. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

- Deci, E.L., Olafsen, A.H. and Ryan, R.M., 2017. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior, 4, pp.19-43.

.svg)